Memories and Hardships of a Pilot on Cruiser Missions

Catapult Launch Cast_recovering Flying_conditions

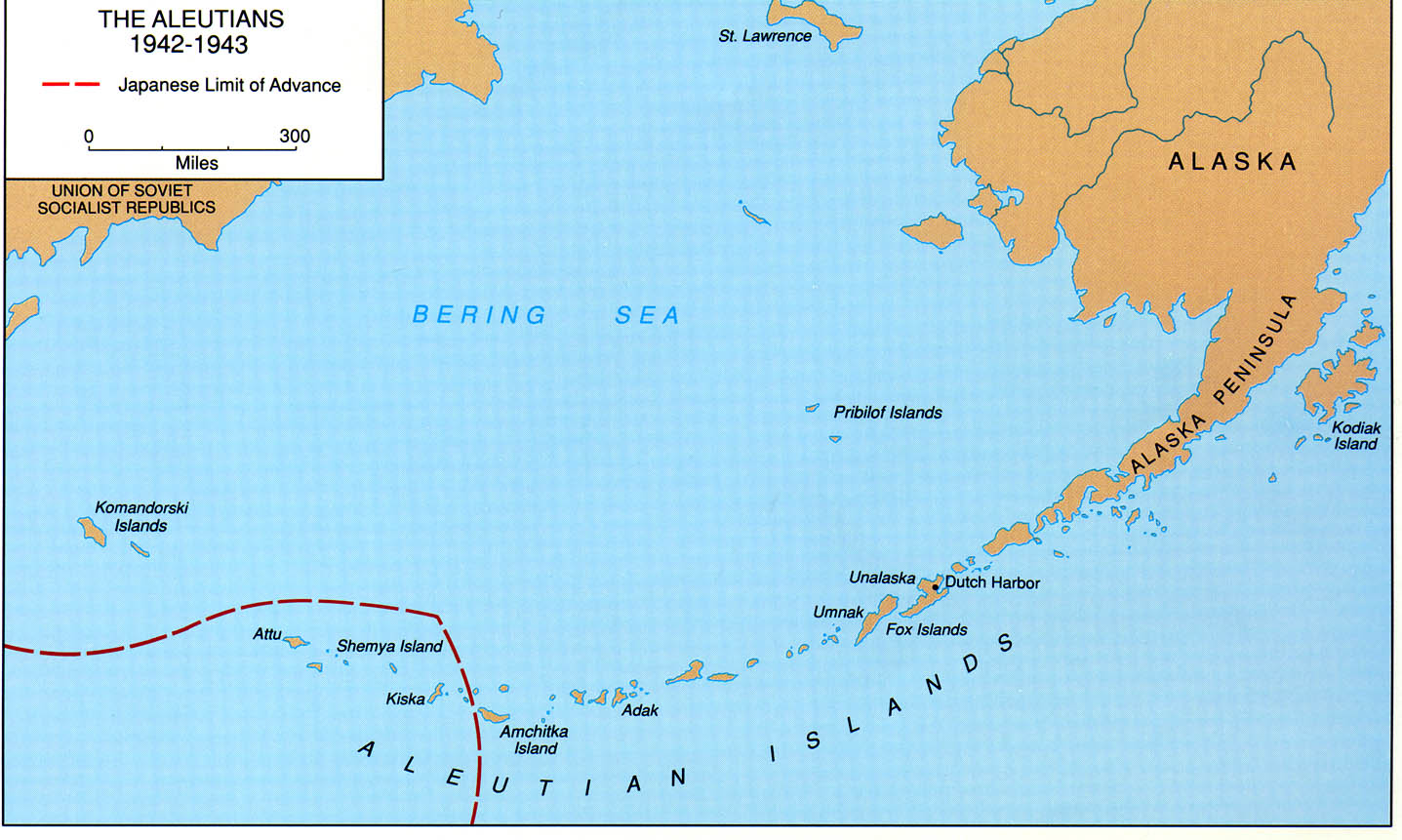

Aleutian Campaign early June

1942

memories of: Lt(jg) Raphael Semmes, Jr.

:Navy Scout Pilot attached to USS St.

Louis 1942 On our way north from Midway Island,

I had a conference with Captain Rood about flight operation in the in-hospitable

North Pacific. He agreed to reduce our search missions to not more than

125 miles from the ship, compared with the 200 miles we had flown routinely in

the South Pacific. This and Captain Rood's generally excellent knowledge of our

capabilities and limitations did much to make successful flight operations

possible. Even so, much of our five months in the Aleutians was frustrated by

bad weather. In July, the task group made several unsuccessful runs against

Kiska where the Japanese had landed and were establishing a base. The weather

was so thick we never saw land, and the enemy probably never knew we were there.

Admiral Theobald, our group commander, decided to return to Kodiak and regroup,

and remarkably the sun came out and we were blessed with beautiful crisp days. New Machine Gun Design: We in the aviation unit used the interval to install the

latest invention of Ray Moore, the unit's gunnery officer. He had discovered

that the fixed firepower of our seaplanes could be doubled by installing an

extra 30-caliber machine gun on the top wing. The "hold down" bolts of the gun

just fit the holes in the wing designed for a camera gun installation. By

running a lanyard from the gun to the cockpit, the pilot could give a yank and

start firing. Best of all, the bullet path cleared the arc of the propeller by a

couple of inches. The result of firing them both together was startling. One gun

let go with a fast and furious rat-tat-tat; the other seemingly much slower and

more sedate. The effect on our morale of putting the extra gun on our old

seaplanes was immediate and favorable. It gave us just the lift we needed to get

out of the doldrums and on with the war. We felt sure we could fix those Kiska

Japs now, in spite of the weather and the "zero" fighters on floats which the

reconnaissance pilots had told us the Japs had now. We decided to keep our Moore

machine gun installation to ourselves. The Bureau of Aeronautics might not look

favorable upon our modification. Kiska Adventure: We were planning another Kiska run and this one had to work. Admiral

Theobald's staff called in the aviators for a special briefing on our part in

the new operation. Each cruiser (there would be a total of five) would launch

two planes to act as spotting planes for the bombardment of the Jap base. Upon

the completion of the bombardment, we would be recovered if conditions

permitted. Otherwise we would be directed to fly to Dutch Harbor (600 nautical

miles) and since this would be beyond our range after flying a spotting hop, the

plans called for a small seaplane tender to hide in the island group halfway to

Dutch Harbor to refuel us. It was hoped that this extreme would not be

necessary. There would be no friendly fighter air

cover for the operation because Kiska was far beyond the tactical radius of the

Alaskan based army fighters, and no U.S. Navy aircraft carrier could be spared

from the operation just now beginning in the Solomon's.

Japanese Submarine, running at hunting speed Submarines were a constant worry and were always in our thoughts. Several

enemy subs had been sighted in Aleutian waters and we felt sure there were some

around now. As far as we knew There would be no friendly fighter air cover for

the operation because Kiska was far beyond the tactical radius of the Alaskan

based army fighters, and no U.S. Navy aircraft carrier could be spared from the

operation just now beginning in the Solomon's. The short time remaining before the bombardment passed swiftly. Early on the

morning of August 7, 1942, the force was south of Kiska and ready for the

run-in. The exact time of the action had not been set, but would most likely be

determined by the weather. The weather seemed to play the leading part in

whatever went on in this strange land. As if to emphasize its importance, we ran

smack into a thick fog bank when thirty miles from Kiska, but Admiral Theobald

was not to be denied this time. We steamed onward, passes alternately through clear spaces and fog banks. We

wondered if our previous abortive attempts in this area had alerted the Japs,

and if they would be lying in wait for us. They had plenty of surface ships to

spare, some for Kiska support, although the Battle of Midway had hurt them badly

in carriers when they had lost four. They were known to have a powerful

undamaged battleship force, whereas our own had been badly mauled at Pearl

Harbor and was not now a factor in the Pacific War. St. Louis aviation unit remained at flight quarters most of the day of

the run-in. Periodically, the planes would be warmed up so they would be ready to go on

short notice. Ray Moore was the pilot to go in the second plane and we were

beginning to get a little nervous with anticipation. Finally, word came down

from the bridge talker that we were really going in, and the planes would be

launched in about fifteen minutes. The indecision was over and the weather

seemed not so nasty now. I told Chief Pepin to top off the planes with gas since

they had been turned up many times and had probably used several gallons apiece

in the process. It must have been a premonition of need. -- I had never felt it necessary to

top off the tanks before if they had been run down a bit but now it seemed very

important. Ray and I climbed into our planes and got ready for the catapulting. My

radio-gunner was Norman, and Gibb was going with Ray. We were launched at 1745

local time. The other cruisers also catapulted their aircraft, and within five

minutes the ships had disappeared from sight in another fog bank. Ray and I

climbed to 2000 feet, which was just above the cloud layer. Two planes from the

cruiser Honolulu joined up with me and we flew around in formation waiting for

the ships to run into a clear area. We couldn't see anything over the sea or

land. Finally, I decided to head north and see if I could make landfall. We

broke out of the overcast over Kiska near Vega Point. It was a strange feeling,

to see at last this Jap-held territory after our struggle to beat the weather to

get here. I proceeded back to the ship and found her, while passing through alternate

layers of fog and clear. I passed the bearing of the harbor to the ship and we

remained circling in her vicinity till she cleared the fog bank about ten miles

off the Kiska South Coast. I led my plane section to an area where there was

some chance of spotting. Honolulu's planes broke off and went about their

own business. We could see the hill around Kiska Harbor all right and we had

enough altitude, but the harbor itself looked like a mass of fog.

Aleutian island string of Islands Japanese fighter planes sighted: At 1940 our ships opened the bombardment. They were firing full salvos and we

could hear the firing above the noise of our own engines. Ray and I flew over

Little Kiska Island and climbed to get above the overcast. We were looking for a

hole to spot through when we saw the leading destroyer shift fire to

anti-aircraft bursts. We saw the plane she was firing at, and another one above

us commenced a diving approach toward us. I was at 2000 feet and commenced a

steep power spiral through the overcast, and leveled off at 200 feet to find

that the fighter had not followed. We were in the clear now and flew toward the

destroyer group, but we could still see nothing in the harbor. Another fighter

was sighted ahead, and as he came in he was taken under fire by a destroyer and

then he turned away. During this time, all ships were firing on schedule and

they would occasionally take an enemy plane under fire. At 2010, the ships ceased firing and changed course. We flew to St. Louis and

began to circle. Almost immediately she signaled to "proceed as previously

directed", which meant for us to fly on up the chain to Dutch Harbor via the

small seaplane tender stationed at Atka. We had hoped for recovery by the ship

as we had already been in the air for the two and a half hours. Also, there was

only about two hours of daylight left not enough to reach Atka. There was

nothing to do but get as far along our course as we could before nightfall, so

we continued to climb until we broke out of the overcast at 3000 feet. We found later that the ships had feared a bombing attack at recovery time

and Captain Rood did not think the ships would have a chance to slow the ship to

pick up their planes. He had sent us the signal to go ahead to give us a little

head start. Actually, the bombers returned to base without attacking and the other

cruisers did recover aircraft. Thus, Ray and I, and the radiomen, were alone now

on our "Aleutian adventure" and Dutch Harbor was 600 nautical miles away. The

small island we had intended to take departure from was completely obscured, so

we were in some doubt as to our position. We never did get a good point of

departure, but took up the prearranged course of 084 degrees and hoped we were

not far off at the start. About 2100, Sugar Loaf Head was identified and we knew

we were pretty close to track, though somewhat to the south. We passed close to

Tanaga Volcano and started to land off the coast, as there was a break in the

overcast and we could see the island short. Tanaga Island Location: I took one look at that Tanaga coastline and it looked so rocky and

uninviting that I decided to go on although it was already after sunset. We set

course in general direction of the next island, Kananga, found a hole, spiraled

down, and landed about halfway between Tanaga and Kananga. I cut my engine and

prepared to wait out the night, which turned out to be one of the strangest I

ever spent. Ray Moore had landed with me and now the two of us were riding the

waves about 100 feet apart. I had arranged with Ray before landing that we would

try for an 0700 takeoff the next morning. The landing had been made at 2230, and in the beginning the weather began to

clear with stars overhead. About midnight, a dense fog descended and the air got

much colder. I lost contact with the other plane. The sea was not very rough,

but there was a moderate swell which made the seaplane pitch a great deal. The

excitement of the day and hour had combined to bring an aching tiredness to my

body. Realizing that the real test of whether we could get back would occur on

the next day's flight, I resolved to try and get some sleep. Have you ever been

defeated by the perversity of an inanimate object? Well, I was that night. The

object turned out to be the cockpit hatch cover. The lock, through long usage,

had picked this moment to become sufficiently worn enough to just refuse to stay

locked. I would close the cover to keep out the cold and leave my hand to hold

the lock down. As soon as I dropped off to sleep, the cover would fly open

again. I tried sleeping with the cover open, but the wind was too cold. Finally,

toward dawn, I got the cover to stay locked by jamming a pencil in the

mechanism. Just after getting this solved, I was awakened from a fitful dozing by

hearing surf breaking. All though of sleep banished, and I was suddenly awake,

visions of being dashed on some inhospitable Aleutian rock racing through my

head. I started the engine and taxied away from the noise of the surf till I

could hear it no more. By the time I had another catnap, dawn was breaking in a

discouraging sort of way. The fog was as thick as any I had ever seen. It clung

to the surface of the water and completely engulfed our plane with its wet

vapor. There was no sign of Ray through this heavy curtain, though he might have

been near for all I know. At 0715, I heard his engine start, run for a while,

and then roar into full power for takeoff. Ray was not far away-maybe 500 yards.

I fired a Very Pistol star to make sure he didn't run me down, but I didn't see

him at all, and soon I was left alone on a cold, fog-bound sea. I called Ray on

my radio but heard nothing. I waited a few minutes to see if the fog might lift

a little, but it only seemed to thicken. I ran over in my mind the choices open

to me-there wasn't really much. I could stay where I was and wait for a weather

improvement, but my previous Aleutian experience reminded me that it might take

days or even weeks. I could take off in the fog and try to navigate somehow to

Nazan Bay on Atka, where the seaplane tender rendezvous was supposed to be.

Well, there was no point in giving in to the weather without a struggle. At 0730, I started the engine, then taxied in circles till the engine was

warm. When all was set for takeoff, the fog remained close to the water and so

thick I had to make an instrument run to get airborne. As soon as we cleared the

water, I put the old SOC in a gentle spiral climb to avoid smashing the

mountains. At 4,000 feet we broke out on top, and the warm sunshine above the

cloud layer was beautiful and so welcome that its effect on our spirits was like

magic. I sighted the summit of Kananga Island Mountain to the north, and from our

relative position calculated that we had drifted almost due south during the

night for fifteen miles in spite of a moderate west wind. We headed north to get

on track and then took up course 084. There gradually appeared some breaks in

the under-cast which began to give me some navigational help. We passed over,

and definitely identified, Kulak Bay on Adak Island. It was a great feeling of

satisfaction to know exactly where I was for a change. Atka Island: We continued on to Atka over about nine-tenths cloud cover and found a hole

just short of where I figured the island should be. I sighted land to starboard

and continued parallel to it until land also appeared to port. It looked like a

dead end, but as I got nearer I could make out a valley between the mountains

and saw water on the other side. We flew through the valley at 50 feet altitude

with a 150 foot ceiling and landed in a bay on the other side. At first I

thought this was Nazan Bay, the rendezvous point, but there was no ship here.

With the ceiling so low, I decided to wait for an improvement before trying to

find the seaplane tender, so we anchored close to the shore at 0915. Norman and

I were both tired after our almost sleepless night on the open sea. This bay was

calm and we both fell asleep without difficulty, sleeping for some little time. After awakening, I found that the ceiling had improved a little and it

appeared that we might be able to scout around to fix our position, and with

luck find our refueling ship. We took off and investigated the coast of the island

very closely. I decided we were definitely on the SW coast of Atka, so I landed

to make out a position report to send to St. Louis on the slim chance they might

pick it up. While I was working on the report, I had Norman check our float gas tank. We

were using it now as I had flown the other tanks dry. We carried a stick with

which to sound this tank, and it showed that we now had 20 gallons left. We had

taken off with 170 from the ship only yesterday. So much had happened that my

shipboard life was beginning to fade into unreality-surely it was longer ago

than yesterday. We got airborne again and streamed the trailing wire antenna for our radio.

Norman sent the message giving our position and I wondered, as I listened on my

earphones to his expert rendition of the Morse dit-dah's, if anyone anywhere

received it.

At 1430 came a break which changed the outcome of this flight. I sighted an

old type destroyer about twelve miles off the coast and almost feared a mirage,

it had been over sixteen hours since I had last glimpsed any human being

(besides Norman in the rear seat). The last had been Ray Moore as darkness had

descended the night before. The ship was still there, so I figured it must be

real and maybe it was our refueling ship. As we neared, I identified myself and had

Norman send the flashing light: "Do you have gas?" The ship sent back, "Can you

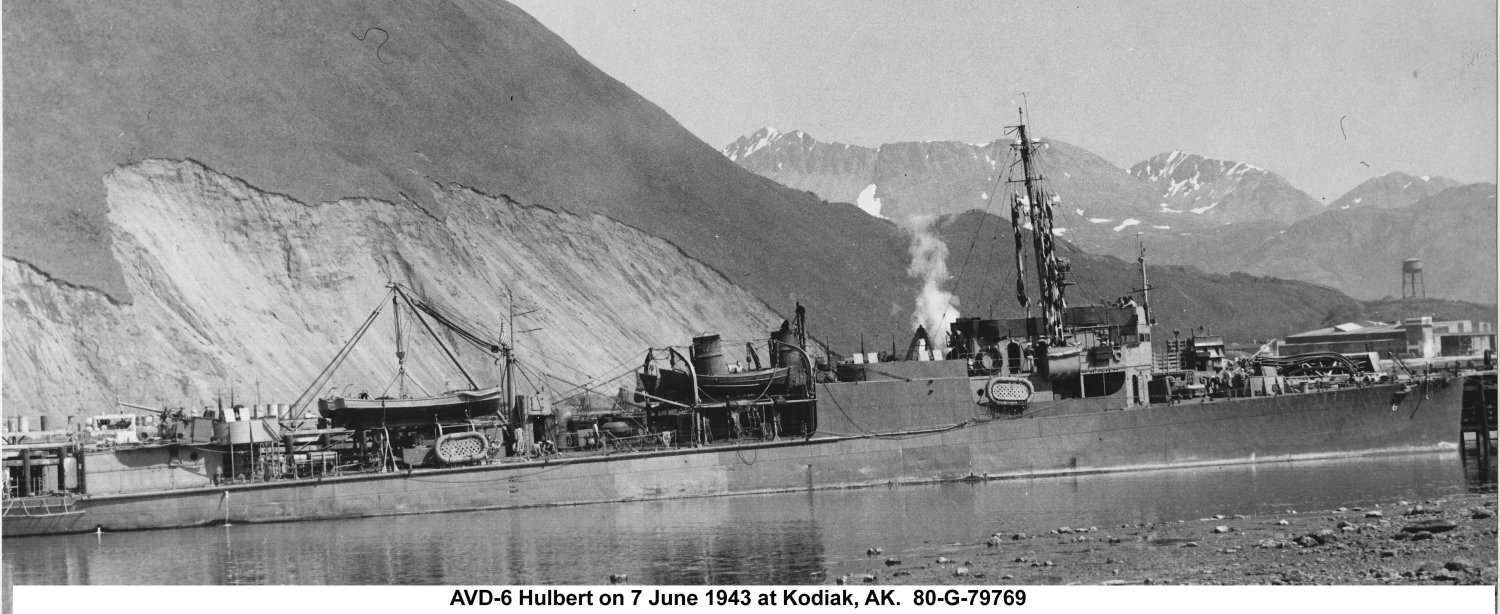

land?" We answered the question by acting it out. We landed and taxied to the fantail of the ship which had now stopped. It did

indeed turn out to be our refueling ship, the USS Hulbert

(AVD-6), and a more

beautiful sight I have never seen. She refueled us (we were now down to five

gallons- enough for about twelve minutes of flying) and also send over by line

hot coffee and sandwiches which were most welcome. The captain of the ship gave

me the latest weather forecast which read fog all the way to Dutch Harbor, now

about 300 miles away. He said if I was doubtful of making it, he would take

Norman and me aboard and sink the plane. It was tempting, but after twenty-one

hours in the plane, from the Japs at Kiska through the Aleutian fog to here, it

was just not the way to end a flight. It was 1515 by the time I was ready to take off, with the plane so heavily

loaded that I could barely get it flying in the calm sea. Regardless of what

else happened on my attempted flight to Dutch Harbor, I should not have fuel

trouble because we were now loaded to 170 gallons again. After some difficulty getting airborne again with the heavy load in the

smooth sea, we turned northwest to seek the Naval Station at Dutch Harbor.

A

little of the Flying conditions

experienced by Lt(jg) Semmes It became apparent soon after leaving the Hurlbut that I would have to go

above the overcast. Even though there were some areas of good visibility, there

were others of practically none at all, and I had to fly as to avoid running

into these islands whose mountains reached upward 7000 feet above the sea. I

passed Sequam Island abeam while flying just above the overcast at 6000

feet, and almost an, hour later passed the first of the Islands of Four

Mountains. The overcast was high now with no holes anywhere. The flying had

become very dreary and depressing as we were now between two solid dark gray

layers. No sign of the earth below or the blue sky which must be above

somewhere. I was carrying a 20 degree drift correction which I had gotten from

an estimate from drift along the Four Mountain islands. This correction,

which quite possibly was off to some extent, could drift me over the islands or

out to sea. I was sorely in need of a break to prove my navigation before trying

a letdown through 6000 feet of fog. The layers' we were flying between gradually seemed to merge. In looking

ahead, or in any other direction, nothing could be made out in the gray same-ness

of the clouds. There was no longer any cloud horizon to help me in keeping the

plane level. I was strictly on instruments even though the plane was not

actually in the clouds. Should I climb up on top, as I had after the night on

water at Kanaga? The heavy thickness above might extend upward far beyond our

ability to climb. Also, once in that grayness, I would have no warning if

mountain peaks should be in our path. A descent through the fog carried

the same danger of running into the

land. It was better to keep this altitude where I at least had a little forward

visibility to give warning of danger ahead. Time seemed to drag interminably. I

would glance at the clock on the instrument panel, then fly on for what seemed a

great interval, to find at next check that a only a mere three minutes or so had

gone by. When my log showed the Umnak Coastal Plan was due abeam by dead reckoning at

1755, there was still nothing but thick gray clouds to see. At last, after

flying nearly an hour without seeing anything but clouds, there appeared a

marvelous funnel shaped hole in them, going down steeply all the way to the

ground. At the bottom of it, like some scene from an unlikely movie, was the

Army base at Umnak Island. I was right on track after all! Before the funnel had

a chance to dissipate, I dived through it so fast that I rattled the wings of

the old SOC and pulled out at 500 feet over the glorious land.

Curtis Seagull (Soc3) catapult scout plane

#Return_to_Top The rest of the way to Dutch Harbor was managed under the

clouds by picking a careful way along the south coast. Norman and I were

relaxing a bit for the first time we could remember. I had my fill of the

mixture of fog and mountains and felt no desire to climb through that stuff

again. I finally got out of the cockpit for the first time in twenty-six hours,

including twelve and a half hours of flying. Ray Moore was at the dock to meet

me and greeted me with, "Who do you think you are, Lindbergh?" I found out that

he had found the re-fueler, then joined up with PBY patrol plane returning to

Dutch Harbor, and flown wing on him back to base. Kodiak Island Base: Ray and I waited several days before getting orders to rejoin St. Louis at

Kodiak. We flew together up the chain the rest of the way without incident. It

seemed somewhat mild after the first 600 miles over the uninhabited and deserted

sea. I felt my Aleutian adventure drawing to a close ... nearing the entrance to

Kodiak Harbor, we sighted St. Louis down below, by a strange coincidence

arriving at the same time as we. Flying nearer, we let them get a good look at

us, close enough to read the side numbers. They recognized us all right. I could imagine Captain Rood up on the bridge

seeing us for the first time since we had catapulted into our adventure a week

before. The signal bridge began sending a message by blinker, which I knew came

from Captain Rood. Norman and I read it together. It was simple, but complete

and it got a wealth of meaning into just two words: "Welcome home." When St. Louis, in company with the Yorktown

and Enterprise groups, arrived at

Aviation Facilities:

I would like to describe the excellent aviation facilities that the cruiser St. Louis and her sister ships had. As you will recall, all the battleships lacked any storage place for the aircraft other than the main deck and the catapults themselves. There was no protection from wind, sea, or gun fire (either from the enemy or from your own ship).

The first treaty cruisers of the Indianapolis class managed a considerable improvement by going to hangars on the main deck amidships, and elevated catapults requiring a long lift-up by crane for any plane moved from either port of starboard hangar to be launched. The St. Louis class seemed to reach the ultimate of efficiency in hangar design to facilitate air operations.

This was possible because the ship had a high freeboard aft, and a square stern giving an excellent storage space where all four planes could be taken below and covered over with a sliding hangar cover. During heavy weather or times when flight operations were not expected, the planes could be worked on in comfort below decks. The key to this was building into the airplane elevator, and hangar deck itself, a guiding track system for handling the small-wheeled carts in which the main pontoon of the SOC rested. If flight operations were expected, one plane would be hoisted aboard each catapult while the other two remained in the hangar with wings folded. After the launching of the first two aircraft, the others would be brought up in turn, the wings unfolded and they would be placed in position for launch. If all went very well, all four planes could be airborne in slightly over four minutes from receipt of the signal "launch aircraft".

Memories "Cast" Recovery"

The more usual recovery, the cast type, involved a ship's turn of 90 degrees through the wind line and was used when a choppy sea needed smoothing out to make a landing place. This slick gave a relatively good water for the plane to touch down while landing into the wind. As soon as the plane slowed, which was quickly in a seaplane, the pilot turned toward the trailing net and taxied aboard until he felt he as in position to cut his power. If he managed this successfully, the plane would drop back, but a spring-loaded hook on the bottom of the pontoon would catch into the webbing of the net and tow the plane along until it could be hooked on to the crane for hoisting aboard.

Back and forth turns through the wind line by the ship would make additional slicks for the other planes to land in their turn. It was the job of the radioman gunner to stand over the pilot's cockpit and unrig the sling from its wing stowage, then effect a mating of it with the crane hook while the plane was bouncing on the net and the hook was swinging to and fro. A good juggling act was required when sea conditions were adverse.

During this phase, the pilot held onto the radioman's legs to keep him from falling overboard. The hook-on was a critical step, but the hoisting could be a bit on the exciting side, particularly if the ship was rolling very much. To prevent the pontoon or wings from smashing into the fantail, the V-division aircraft handling crew would man long poles, with padded U-shaped ends, to steady the plane as it was being hoisted up the considerable distance from the sea to the deck of the St. Louis.

Built-in small, flexible cables were also attached to lines from the ship during this hoisting phase. There were occasional mishaps, but the SOC's were ruggedly built and most damage was minor and could be repaired by the excellent mechanics and metal smiths aboard.

Memories

The CATAPULTING of the St. Louis aircraft was accomplished through the use of the 5-inch powder charges rigged to accelerate the launching cart down the greased track. The catapult officers were instructed to launch the plane on an up-roll of that side of the ship. The aviators sometimes complained that for perversity they would launch on the down-roll instead. The launching itself was a sudden and violent affair. The airplane engine was revved to full power upon signal of the launching officer. The pilot locked the throttle quadrant tight, gave a "launch ok" signal, and rested his head against a cushioned back rest. Shortly thereafter, there was a muffled boom and a rapid acceleration from zero to sixty knots in the in the sixty feet of catapult run. When the plane got to the end of the catapult, two hydraulic bumpers stopped the cart and the pontoon, airplane, pilot, radioman, and assorted equipment was now flying over the sea. Flaps were retracted as speed was gained and the mission was underway.

Return to Top